Welcome to Freaky Friday, the only time during the entire week when you can relax and read about books that can’t hurt you anymore because they were written long ago on strips of bark.

“As the years go by, our friendship will never die. You’re gonna see it’s our destiny. You’ve got a friend in me.” So sang Randy Newman in his theme song for the hit 1995 Pixar film, Toy Story, about a young boy imprisoned by his talking toys who try to foil his every step on the road to adulthood. It’s harrowing to watch this young man attempt to reach adulthood while surrounded by yammering, clacking, animated toys, many of them backed by major corporations, who view Andy’s maturity and subsequent freedom as an existential threat to their existence. People around the world identified with Andy’s struggle against these tiny tyrants and the movie spawned two traumatic sequels, Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3, which made the threat clear: if you were unable to destroy your childhood toys, or at least pawn them off on a smaller, weaker child, then they would do everything in their power to keep you enslaved to their own desires, and if you tried to escape they would pursue you to the ends of the earth—relentless, untiring, unstoppable. They will not rest, they will not sleep, no matter where you go they will follow, even “To infinity…and beyond!”

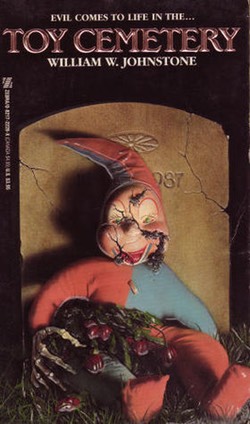

Is it any surprise then that worst cemetery of them all—worse even than the pet cemetery or the Neil Gaiman cemetery—is the Toy Cemetery?

Jay Clute is an average, everyday Vietnam vet haunted by memories of childhood trauma, driving back home to the sleepy Southern town of Victory, Missouri with his vivacious nine-year-old daughter, Kelly, to sort out the estate of his recently-deceased Aunt Cary. No sooner has his neighbor, Old Man Milton, welcomed him back with a hearty, “Welcome home, asshole,” than the local bank owner’s nubile teenage daughter has given him a “rubdown,” he’s almost run over a tiny, living doll crossing the street (that flips him off with both fingers), and children have called his phone to giggle eerily and whisper, “You should have stayed away, Clute. Now it’s too late.” His reaction to these grim omens?

“He began to wonder what they were going to have for dinner.”

Welcome to the Olympics of horror cliches, where splitting up is the only way to do anything, conversations inevitably end the second shocking revelations are teased, and a tiny living doll screaming and stabbing you in the foot is dismissed as “Only the wind.” If Jay was not in a horror novel he never would have come back to this town where his entire family went missing one day when he was 17 and where he’s haunted by memories of “that awful night” when he and some high school friends snuck into the Old Abandoned Clute Place and were attacked by ghosts. But, as the police say, “Lots of folks just take off and are never heard from again,” and as for the ghost attack, he’d prefer not to think about it.

Not an option. Within a few hours of arriving in Victory, Jay discovers that the two major local landmarks are an enormous, locked doll factory in the center of town run by an obese pedophile named Bruno Dixon, and a high security hospital/mental institution/underground research facility that houses the “products of incest” which are, apparently, enormous man-monsters with apple-sized heads and superhuman strength. Like toys, incest runs amuck in Victory. Jay and his daughter almost hook up their first night in Victory, saved only when the crosses they’re wearing (that Kelly got from a kindly old blind priest named Father Pat who calls everybody “my child” and feels your face to know if you’re smiling or frowning) clink together.

Only the power of Jesus can make Jay unattractive to women. His ex-wife Piper (“one of the nation’s top models,” a character reminds us) returns in the middle of the book to tell him that she never stopped loving him, and post-rubdown Jay goes on a hot date with Deva, his high school sweetheart, who has grown up and made good (“I write romance books under the name of Yvette Michoud and I own the local newspaper,” she purrs). Deva knows something fishy is afoot in Victory but she just isn’t ready to talk about it yet, not even when she and her daughter, Jenny, almost hook up thanks to the incest rays getting beamed all over Victory by Satan, who lives in the hospital and goes by the name The Old One, and has his needs catered to by a group of men known as The Committee.

Despite these ominous omens, no one is alarmed. When they see moving dolls they blame it on dust in their eyes, when they’re attacked by animated sheets they blame it on the wind, when houses slam their doors and windows open and shut over and over again they decide they’d better not mention it, and when someone discovers the secret of the living toys they decide to explain it “later” because they want to go and pray.

“If any of us knew anything,” one character cries, “We could do something about it!”

A lack of knowledge might be less of a problem than a lack of initiative. A teenager’s head explodes, and Jay is told to go home and not worry about it. Teenage boys follow Kelly and Jenny through town, jerking on their inappropriate boners in public until Kelly fights them with karate and kills one of them by throwing an axe through his head. No one cares. Deva has a gun collection and Jay takes her shotgun and runs around blowing people away without ruffling any feathers. Tiny living dolls of clowns, soldiers, Barbies, and Kens attack people with miniature swords and spears, hacking away at their ankles, only to be dismissed as something no one can afford to worry about right this minute.

The only person who seems to know anything is the ghost of Aunt Cary who materializes halfway through the book to call Jay “piss-pants” four times in a row, then have ghost incest with her dead brother in front of everybody. It turns out her dead brother is a ghost werewolf who can only be killed with a stake through the heart, which happens. Then Aunt Cary explains the plot, but she entirely leaves out the role played by the living toys. At this point, reading the book becomes like trying to drive in a post-concussion haze: the harder you focus the more everything slips away, swirling just out of reach in an insanity vortex.

See, there are two toy armies. One army lives in the toy factory with Bruno Dixon where Satanic kiddie porn movies are made, and the other are broken and injured toys who seek shelter in the Old Clute Place where they kill and eat neighborhood pets, tap out “Help us” in Morse code (prompting Deva to hit the road, “I’m getting out of here, Jay…That’s enough for one day”), and take orders from the French toy soldier, Richlieu. Sometimes these toys are evil, too, much in the same way that sometimes The Committee wants to kill Jay, sometimes they are forbidden from killing him, and sometimes they just disappear from the book for hundreds of pages. Jay finally breaks through to these misfit toys when he is so moved by the death of a toy French Legionnaire that he cries on a sad clown doll who cries back as Jay’s tears land on its polka dot suit and then all the dolls are crying and they rise up in model airplanes and bomb the evil toys…some of whom are local citizens who’ve been turned into doll-sized humans and others of whom are dolls who’ve been turned human-sized. I don’t even know anymore.

The book draws to a close as every single female character is revealed to not only have a secret doll collection but to also be possessed by Satan and totally horny, causing Jay to pick up a local newscaster as his latest honey and go on a killing spree. He’s outnumbered by evil, living, human-sized dolls but saved at the last minute when he falls down an abandoned mine full of rattlesnakes and then runs out of town and comes back with the FBI who vacillate between believing him, getting stabbed to death by local children, or trying to arrest Jay for being crazy. And I’m leaving out Stoner, the geneticist/psychiatrist who wields a mean bow and arrow, the elderly man who turns out to be a pistol-packing OSS agent, and how Jay stops time by shooting a clock.

By the end of this book, nothing makes sense and no one knows anything. The only things you can rely on is that women are treacherous monsters possessed by Satan who never listen, and that toys are really, really terrible.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, just came out this past Tuesday. It’s basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.